Silhouettes are said to have been the first form of art, with their origins in tracing the shadow of a person upon the ground. The traditional dark silhouette with a light background we think of today had its heyday in the second half of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century. It emerged as a popular portrait medium in response to miniatures or oil portraits. Painted portraits were expensive and required multiple sittings. A skilled silhouettist could complete a silhouette in just minutes.

Most were made with paper and are about the size of a modern snapshot. Many examples are in profile, which was thought to capture the sitter’s likeness more easily. A late 18th-century physiognomist, Johann Lavater, promoted the idea that a person’s outward appearance could provide insight into their character, and that the best way of evaluating was to look at a profile of the person.

There were three different techniques that are easily recognizable. Many early silhouettes were painted or drawn with pen onto a light background. The outline would be laid down and then the image filled in. Many American silhouettes are hollow-cut; that is to say, the image is traced and the positive image removed. The negative image is then adhered to a dark backing of cloth or paper. Finally, there are cut-outs. Both busts and full-figure silhouettes are prevalent. A silhouettist would draw the profile on a piece of paper, and then cut it out. It was then adhered to a light background.

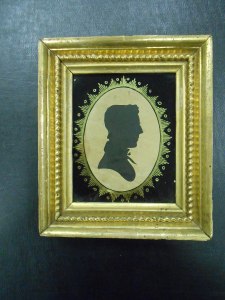

Peter Richards in 1868. White chalk lines and black pen lines add detail to the silhouette in the hair and dress.

The Historical Society has one example of a cut-out, and the rest of our collection are hollow-cut. The cut-out silhouette has a very interesting story. It was created by Martha Ann (M.A.) Honeywell, a native of New Hampshire, who briefly worked at the Peale Museum. She was born without hands and with only one foot. She created her silhouettes by holding the scissors in her mouth and steadying them with her toes!

Many silhouettists worked free-hand, either drawing or cutting. Some set up lights and papers to be able to trace the sitter’s shadow. Still others used the assistance of a machine. One such machine, the physiognotrace, was developed by Isaac Hopkins and used in Philadelphia in the museum of Charles Willson Peale. It had a metal bar which literally traced the face of the sitter. The Historical Society has a variety of silhouettes from the Peale Museum. They are marked with a blind stamp “MUSEUM” below the curve of the bust. Below are some examples.

Four silhouettes of the Shippen and Burd families. All with “MUSEUM” stamps, indicating Peale Museum origin

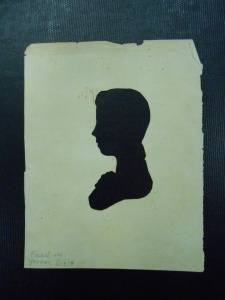

Image of a young boy found in Yerkes family bible with “MUSEUM” stamp, indicating Peale Museum origin

The tracing machine at the Peale Museum could be operated by an amateur visitor to the museum, or for eight cents, Moses Williams, a former slave of the Peale family, assisted the visitor in creating their silhouette.

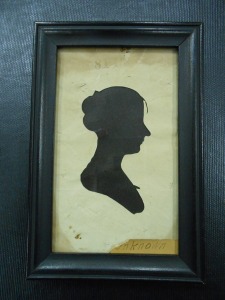

Unknown female, with blind stamp of an eagle and “PEALE’S MUSEUM” indicating later Peale Museum origin

There were other well-known silhouettists who traveled the country and even across the Atlantic Ocean meeting the demand for silhouettes, like August Edouart. John Miers’ work appears early, even before a silhouette was called “a silhouette.” They were originally called profiles, shades, or shadow portraits. There’s no definitive story of how the term silhouette came to be, but Etienne de Silhouette, a short lived Minister of Finance in France in 1759, was known to be both a cheapskate and a fan of cutting profiles.

The Historical Society will have a small exhibit of all many more of our silhouettes at Headquarters in the upcoming weeks.

Source: http://cool.conservation-us.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v18/bp18-07.html